Some histories of Livingston state that a Haitian man by the name of Marcos Monteros founded Livingston and some have even combined the names to form “Marcos Monteros Sánchez Díaz”. In addition, some list the founding year as 1802 and others as 1806. There is documentary evidence to suggest that the Garífuna were in Belize at least by 1802; a letter written by Mr. Cunningham from December 17, 1802 expresses his desire that these “gente mas peligrosa” (‘most dangerous people’) be expelled from Belize. This statement was not without provocation; the Garínagu had publicly declared their allegiance to the Spanish by helping them defend the coasts against British ships and their presence in that British colony, although in search of logging work, was most unwelcome.

Interestingly, the actual name “Marco Sánchez Díaz” is not present in any of the many Livingston Garífuna folk songs (one song from Belize does exist) passed down through the generations; it is only in the past decade that his name was mentioned in a song written by Garífuna recording artist and Livingston resident Juan Carlos Sánchez. In addition to this song, a few years ago, restaurateur and spiritualist Mariano Gotay felt himself possessed by the spirits of the áhari, the ancestors, and spoke as if in a trance and mentioned the name of Marco Sánchez Díaz. Of the Garínagu who witnessed the event, one individual wrote down this utterance which has become a standard prayer in many Garífuna ceremonies. Over the years there have been attempts (including my own efforts to link the Haitian lieutenant Marco Antonio to Marco Sánchez Díaz) to validate his existence through new discoveries in historic texts.

Traveling in the mid-19th century, French traveler Alfred de Valois wrote about Blacks in the Caribbean and Central America, and dedicated a chapter of his book, Mexique, Havane et Guatemala (1861) to Livingston (“Lewingston”). In it, Livingston in 1860 was equated to that of an African village, consisting of fifty houses with 150-200 residents who came from the (Lesser) Antilles and from Hispaniola after the (Haitian) revolution, wandering the (Belizean, Guatemalan and Honduran) coasts in search of a place to build their villages. This text introduces the reader to an elderly man named Marco who speaks perfect French and is remarkably well-known and respected all over the region. The author explains that Tata Marco (‘Tata’ is a term of endearment for an elder or a nickname for ‘great’ (-grandfather)) claims to have been the “governeur of Lewingston” for the past one hundred years (he claims he is 132 years old). The author makes a special point of indicating that the story is legitimate, Tout est vrai dans cette histore, malgré le ton romanesque avec lequel elle est recontée et qui était celui de Tata-Marco (“Everything is true in this story, despite the romantic tone with which it is told and who Tata Marco was.”).

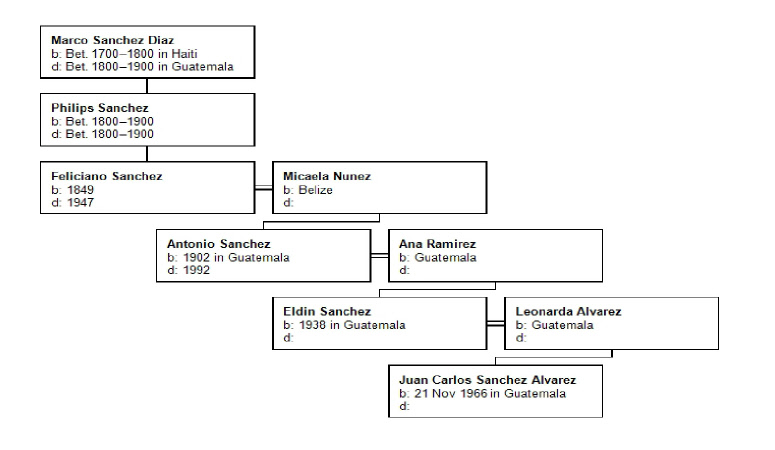

Juan Carlos confirmed that Marco Sánchez Díaz (Juan Carlos refers to him as “Tata Marco”) did indeed settle in La Guaira, as was previously mentioned, where Marco’s descendants also lived, and in fact, on the same property in which Juan Carlos grew up as a boy. At the age of seven, Juan Carlos moved to live with his maternal grandmother in the San Jose neighborhood (in Livingston). Eldin Sánchez currently lives in Livingston.

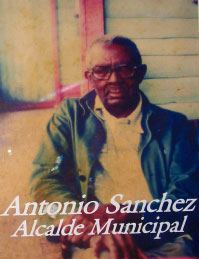

Over a century after this publication, the Garífuna elder Antonio Sánchez Núñez, a curator of Garífuna oral tradition and Mayor of Livingston from 1953-54, declared that the de Valois account was valid because Sánchez Núñez himself was Marco Sánchez Díaz’s great-grandson. Transcribed by Tomas Garcia Zuñiga, Antonio issued a statement about his great-grandfather’s founding of Livingston. Although some of his facts may be slightly imprecise (i.e., there is no evidence that Edward Livingston ever lived in Livingston, nor is there evidence that Marco Sánchez Díaz was descended from Black slaves from France), it is the only known document put forth by someone who knew Marco Sánchez Díaz.

The aforementioned Juan Carlos Sánchez Alvarez is a respected leader and spiritualist in the Garífuna community and internationally known as a composer and performer of traditional Garífuna music. He is a recognized descendant of Marco Sánchez Díaz: